|

Although

Great Britain had exercised authority over "Madawaska" since its founding

in 1785 (administering it as a part of New Brunswick), jurisdiction over

the entire territory was disputed due to the ambiguous wording of the

1783 Treaty of Versailles that set the boundary between the United States

and British North America (Albert [1920] 1985: 90). In addition to the

ambiguity, there was great interest in the timber resources of the region

by both Americans and Britons, and logging operations were underway on

both sides of the river when the State of Maine was created in 1820. In

1826, logging licenses were suspended pending settlement of the border

dispute (Craig 1988: 130). The conflict that arose during the following

years was a source of hostilities between Great Britain and the United

States that ranged from a brief period of armed conflict in the "Bloodless"

Aroostook War, to several years of often acrimonious diplomatic disputes

and negotiations in state, provincial, and national capitals (McDonald

1990). Although

Great Britain had exercised authority over "Madawaska" since its founding

in 1785 (administering it as a part of New Brunswick), jurisdiction over

the entire territory was disputed due to the ambiguous wording of the

1783 Treaty of Versailles that set the boundary between the United States

and British North America (Albert [1920] 1985: 90). In addition to the

ambiguity, there was great interest in the timber resources of the region

by both Americans and Britons, and logging operations were underway on

both sides of the river when the State of Maine was created in 1820. In

1826, logging licenses were suspended pending settlement of the border

dispute (Craig 1988: 130). The conflict that arose during the following

years was a source of hostilities between Great Britain and the United

States that ranged from a brief period of armed conflict in the "Bloodless"

Aroostook War, to several years of often acrimonious diplomatic disputes

and negotiations in state, provincial, and national capitals (McDonald

1990).

John

Baker, one of several Americans from the Kennebec Valley who had begun

moving into the Upper St. John Valley in 1817, became one of the standard-bearers

for claims to the area by Maine and the United States (Albert [1920] 1985:

92-93). On July 4, 1827, Baker organized an Independence Day celebration

from his home on the north shore of the river and raised an American flag

to challenge British authority (Dubay 1983: 26-27). In late September

that same year, Baker, an American citizen, was arrested, tried, in Fredericton,

New Brunswick, and sentenced to three months of imprisonment for rebellious

activities. Prompted by the arrest and desiring to establish the sovereignty

of Maine, the newly installed state government sought action from the

federal government in Washington. John

Baker, one of several Americans from the Kennebec Valley who had begun

moving into the Upper St. John Valley in 1817, became one of the standard-bearers

for claims to the area by Maine and the United States (Albert [1920] 1985:

92-93). On July 4, 1827, Baker organized an Independence Day celebration

from his home on the north shore of the river and raised an American flag

to challenge British authority (Dubay 1983: 26-27). In late September

that same year, Baker, an American citizen, was arrested, tried, in Fredericton,

New Brunswick, and sentenced to three months of imprisonment for rebellious

activities. Prompted by the arrest and desiring to establish the sovereignty

of Maine, the newly installed state government sought action from the

federal government in Washington.

The Governor of New Brunswick, Sir John Harvey,  visited the disputed territory and reported in 1839, "the Acadians of

Madawaska have manifested to me on numerous occasions (and again very

recently) their unanimous and spontaneous desire to remain under the jurisdiction

of New Brunswick" (Albert [1920] 1985: 100). Writings from the period

indicate the inhabitants feared that they might lose possession of their

lands if their territory became a part of the United States (Dubay 1983:

29).

visited the disputed territory and reported in 1839, "the Acadians of

Madawaska have manifested to me on numerous occasions (and again very

recently) their unanimous and spontaneous desire to remain under the jurisdiction

of New Brunswick" (Albert [1920] 1985: 100). Writings from the period

indicate the inhabitants feared that they might lose possession of their

lands if their territory became a part of the United States (Dubay 1983:

29).

|

|

|

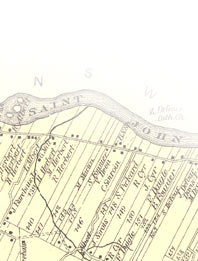

Whatever the wishes of the inhabitants, the boundary dispute was settled

through diplomacy and arbitration. The matter was resolved in 1842 when

Lord Ashburton of Great Britain and Daniel Webster of the United States

negotiated a treaty (known as the Webster-Ashburton Treaty) that established

the St. John and St. Francis rivers as the international boundary above

Grand Falls.

Following the border settlement, some settlers arriving from Lower Canada

preferred to remain on the New Brunswick side rather than cross into Maine

(Albert [1920] 1985: 116). Due to a reduction in immigration, population

increase was slower on the American side during the 1840s and 1860s. The

settlement of the Maine side of the valley did, however, continue to expand.

Allen (1981: 87) summarizes the expansion as follows:

Some people moved up the Fish River along a newly created road to

the south. Also, by the 1850s logging trails penetrated the broad hill

country east of Frenchville, and after 1860 this area received its first

farm families. Ultimately, these back settlements would be spread over

the land some ten miles south of the river. By 1892, the settlement

encompassed Hamlin on the east and St. Francis on the west, but the

general direction of the expansion was to the south. Wallagrass, Eagle

Lake, and Winterville were then well populated.

Expansion to the southeast brought people of French descent in contact

with English-speaking settlers in eastern Aroostook County, and with Swedish

immigrants who had founded the town of New Sweden (1871) and later the

town of Stockholm. On the western extremity of French settlement in the

Valley, near the mouth of the St. Francis River, the French population

came in contact with English-speaking loggers of Scots-Irish descent who

had migrated there from New Brunswick (Allen 1981: 87).

Expansion to the southeast brought people of French descent in contact

with English-speaking settlers in eastern Aroostook County, and with Swedish

immigrants who had founded the town of New Sweden (1871) and later the

town of Stockholm. On the western extremity of French settlement in the

Valley, near the mouth of the St. Francis River, the French population

came in contact with English-speaking loggers of Scots-Irish descent who

had migrated there from New Brunswick (Allen 1981: 87).

According to William Ganong (1901) the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842,

which gave approximately two-thirds of the disputed territory to the United

States, was actually favorable to Great Britain because, based on the

wording of the Treaty of Versailles, the State of Maine had a strong claim

to the entire territory. However, the boundary settlement was unfortunate

in that it divided a compact and homogeneous population between two governments

and created an "unnatural" territorial boundary. Today Maine Acadians

generally ignore the international boundary with regard to family and

social ties. Yet, the St. John River has formed a portion of the northern

border of the United States since 1842. Maine Acadian identity has come

to embrace being both "American" and "Acadian."

|

|